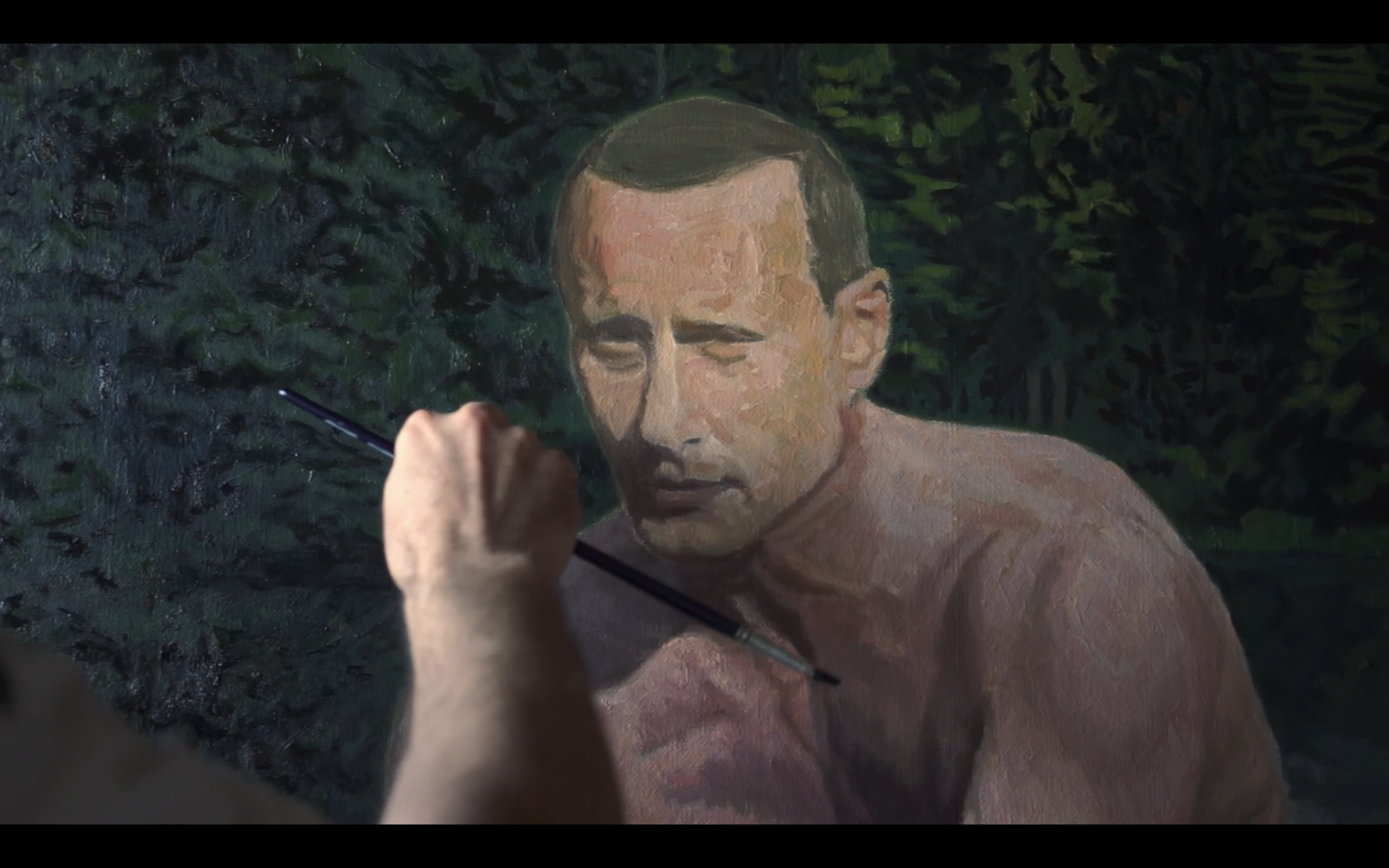

“A Tough Male Portrait” (15:00, film, 2019)

In my documentary “A Tough Male Portrait” (2019-2022) I explore the effects of state propaganda on a patriarchal subject. The protagonist, a tennis coach, decides to become an artist and spends two years on one work – a life-size oil painting of semi-nude Vladimir Putin. The self-taught artist’s dangerous fascination with power and seemingly unlimited belief in its benevolence was (and is) shared by millions of people affected by propaganda and led to the present situation. The film is available to watch upon a request.

The film was part of Steirischer Herbst Festival in 2022.

https://2022.steirischerherbst.at/en/program/artists/3657/ekaterina-muromtseva

Film stills, courtesy of the artist.

‘A Tough Male Portrait’, XL Gallery, Moscow, 10.09.2019 - 15.10.2019

A documentary film with a plot is in the centre of the project; you absolutely need to watch the entire film.

The more visceral the impression of a work of art, the more artless its look, the harder it is to figure out where such an effect comes from. In this case, my final conclusion may seem strange if you omit the whole previous chain of reasoning. Here it is: Ekaterina Muromtseva created a film about the impossibility of non-political art.

I’ll elaborate.

Retrospectively, one can say that Muromtseva is all about the political dimension of art. It can be traced in all her projects, but it doesn’t jump out at you. It is characteristic that Muromtseva usually chooses a deliberately indifferent intonation. One of important methods for her is theatricalizing the action, creating a distance, causing a defamiliarization effect: with magic lanterns, tape winders, puppets. Methodologically speaking, it reminds of William Kentridge, and also Kara Walker, and especially Wael Shawky who relates the barbarities of the crusaders through puppets. In order to have a serious discussion, one needs conventions and props. Trickery, clockworks, 18th century, Mat Collishaw. Muromtseva practices a decorative and somewhat tender ‘artificiality’, through with seeps the heavy meaning of the message: about violence, for example, like in huge watercolour paintings that were also exhibited in XL in the past, where the collective body of the state looks like blurry patterns on wallpaper. In a smooth and as if artificial wrapping, you swallow a bitter pill earlier than you feel it. When you want to spit it out, it’ll be too late.

On the other hand, Muromtseva practices a sort of phenomenological anthropology. Her video ‘In This Country’ is an attempt of looking, with the eyes of uninformed children, into the recent past that instantly develops hyperbolized mythological traits. It’s like ‘Big Trouble’ the other way round (a 1961 animation film about a family breakdown through the eyes of a little girl who doesn’t understand euphemisms that adults use and thus doesn’t lose her enthusiasm). What will ‘this country’ look like if we try to imagine it and put a face to it? Another project of the series is ‘Vasya was here’ exhibited in the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. In this project, as well, documentary records are made meaningful and visualized immediately, out of context, and as a result, we have a portrait of a collective museum visitor that could be restored based on the book of comments and suggestions by archeologists from another planet 100,000 years from now.

In ‘Tough Male Portrait’, both these approaches are applied. This film is a shapeshifter about the wish to do something special and to ‘leave a mark in history’ transforms into monomania. The protagonist is so immersed in his story and so unencumbered by self-reflection that one can only admire it.

The means of defamiliarization is the camera itself that films (supposedly) an artless story of a person who exposes himself: “I’m not a stickler for politicizing art – whatever anyone says, be it Banksy or not Banksy… bottom line is it’s decoration”. It is the wish to be an apolitical artist that becomes a marker of deformation. At a certain point, a transfer takes place: you don’t want to be an artist at all but you don’t notice the falseness anymore.

Then, the political charge of the work shows through the inside, private story.

Because this film is also about blind adoration of a deus ex machina who will turn quite a disorderly life into something consistent, fill it with signs, give it substance. Such an aspiration to justify your (quite horrendous) actions at any cost comes from out of bare necessities of life and looks like a diagnosis of a society, not a single its member. It goes from a particular right idea to a general one. One shouldn’t keep people from … disavowing themselves. They will tell everything about themselves, even more than we expected to hear.

“…at that, I wanted to give him a present of a painting that would probably be made in a contemporary style so that maybe he would like it so much that it would make him a fan of contemporary art if he still isn’t one.”

Looking into such a mirror is painful and enthralling at the same time.

Vladimir Dudchenko